Imagining Christian's 'raiment' (and the Letter to Diognetus) with Vivian's Creative Project

- andydraycott7

- Jan 21, 2023

- 3 min read

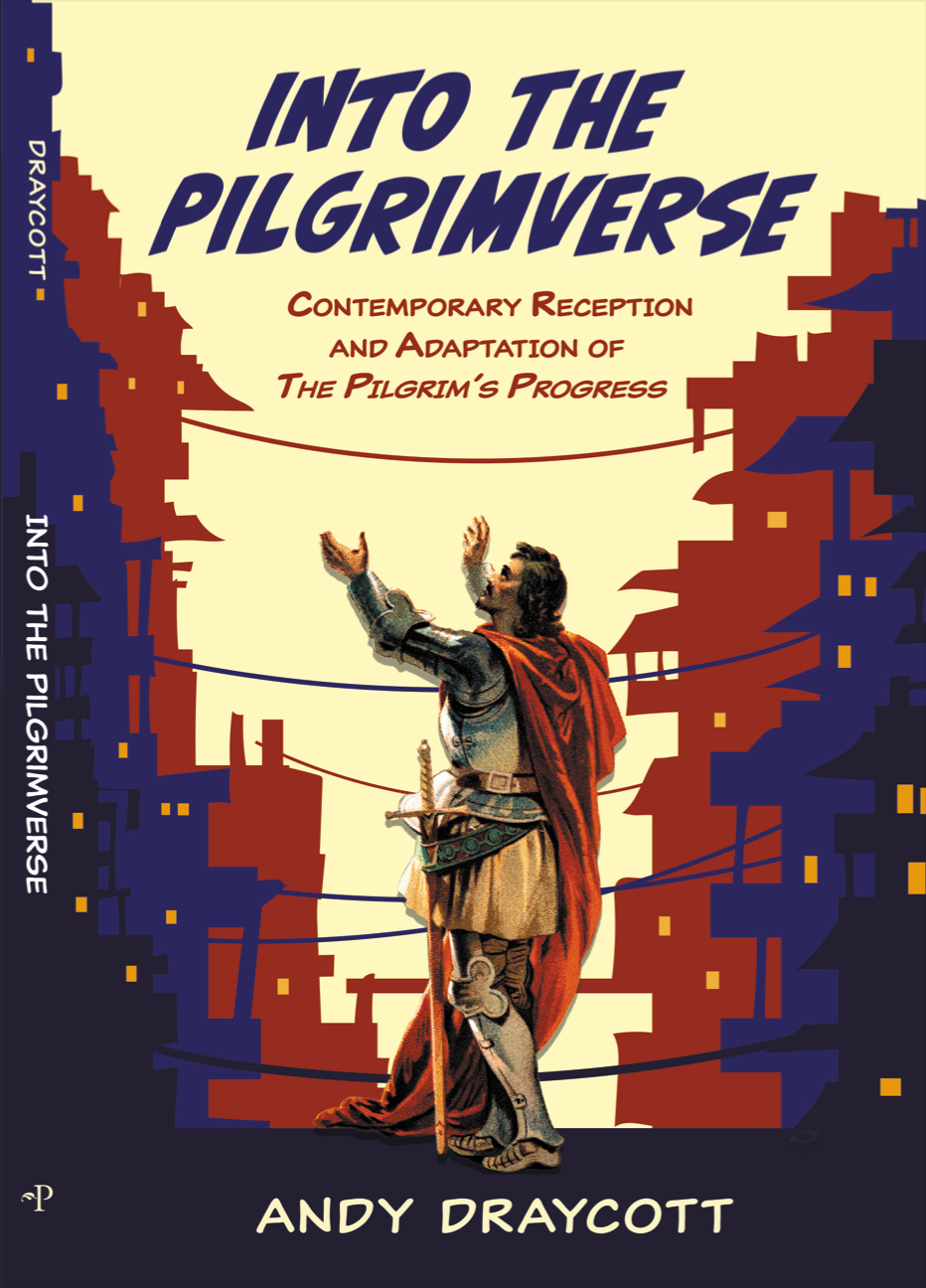

One way that the New Testament depicts conversion is putting off the old self and putting on Christ. The language speaks to what we call 'identity' which we connect in all sorts of ways to appearance. No wonder we make judgments all the time based on how a person presents themselves. We are meant to do so when we meet the man at the beginning of PP Part I. Being clothed in rags fits the lower station in life that seems to characterize the traveler as he meets hostile lords and gentlemen. Bunyan makes clear that his primary intention however is not a reference to economic impoverishment, but sin. He signals this with his marginal reference to Isaiah 64:6, "But we are all as an unclean thing,

and all our righteousnesses are as filthy rags;"(KJV). Iniquities, sin or unrighteousness, are scantily revealing of the shame of failure before a righteous God.

(William Blake captures the raggediness well.)

What joy is it, then, when Christian receives a new raiment at the Cross. Later, in conversation with Formalist and Hypocrisy, we learn that this is a coat of righteousness. That alien, imputed righteousness Bunyan insists on as the key of his Reformational understanding of salvation (This is set out in more detail, within the world of PP, in later conversation with Ignorance, and Great-Heart's exposition of the two natures of Christ and his righteousness, at the cross, in Part II.). No longer filthy rags, but a new coat.

(Screenshot of Christian's new clothes at the cross, from Pilgrim's Progress (2019) dir. Robert Fernandez, Cat in the Mill Productions/ Revelation Media)

What does Christian look like? We'll come back to his armor in another post, but it is clear that he and Faithful are dressed oddly in the eyes of the citizens of Vanity. At the Fair they attract comment by looking outlandish, like foreigners. As 'strangers and pilgrims' (1 Peter 2:11) in the world, as Bunyan alludes to in this encounter, believers, who are not of the world, stand out. By way of dress, Bunyan gets at the distinctives that should differentiate a Christian from wider pagan culture. By way of allegory, and maintaining distinctiveness, Bunyan expresses almost the exact opposite of the early church apologist who wrote the Letter to Diognetus, while making the same point:

For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. For they neither inhabit cities of their own, nor employ a peculiar form of speech, nor lead a life which is marked out by any singularity. The course of conduct which they follow has not been devised by any speculation or deliberation of inquisitive men; nor do they, like some, proclaim themselves the advocates of any merely human doctrines. But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities, according as the lot of each of them has determined, and following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life. They dwell in their own countries, but simply as sojourners. As citizens, they share in all things with others, and yet endure all things as if foreigners. Every foreign land is to them as their native country, and every land of their birth as a land of strangers.

As part of a creative project last semester, Vivian chose to focus on Christian's costume, and the change from his worldly garb to his world-to-come-pilgrim gear. She certainly gets the transitions in styles of dress radically. Interesting to see the interpretative choice to have Christian's new clothes resemble greco-roman attire of the New Testament era:

Comments